Verplaatsingen

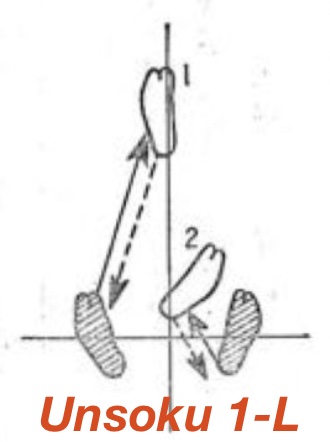

De manier waarop je verplaatst (voorwaarts, achterwaarts of zijwaarts) speelt een cruciale rol bij het behouden van je houding en het effectief uitvoeren van aanval en verdediging. Om snel en effectief te handelen in de split-second dynamiek van gevechten, moet je geest kalm blijven en je lichaam in balans blijven in een natuurlijke houding. Elke verstoring in je houding kan leiden tot kwetsbaarheid. Verplaatsing moet daarom voldoen aan stapmethodes (unsoku) die balans behouden en destabilisatie voorkomen, ongeacht de richting of rotatie.

De basisprincipes van verplaatsing omvatten het coördineren van het zwaartepunt van je lichaam met de voetplaatsing. Je lichaamsgewicht moet altijd in lijn zijn met de voet in beweging, waarbij beide voeten dicht bij de grond blijven. Dit zorgt voor naadloze overgangen in houding zonder het evenwicht te verliezen.

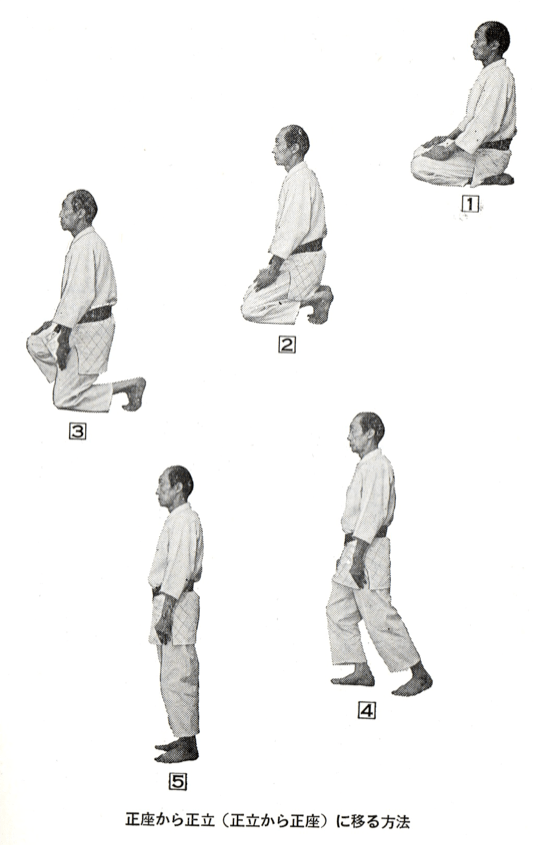

Overgang tussen Zittende en Staande Houdingen:

- Van Seiza naar Staand:

- Buig je tenen onder voor een stabiele basis.

- Plaats gewicht op één knie en til de andere knie op, terwijl je je houding recht houdt.

- Kom geleidelijk overeind in de staande houding.

- Van Staand naar Seiza:

- Zet één voet naar achteren om je lichaam geleidelijk te verlagen.

- Laat één knie zakken, gevolgd door de andere, en ga in seiza zitten.

- Behoud balans tijdens de beweging.

De Verplaatsingen

In boeken als Judo Taiso, Judo & Aikido en Aikido Nyumon van Kenji Tomiki worden verschillende termen gebruikt om verplaatsing te definieren. In Goshin Jutsu Nyumon (20 november 1974) beschreef Tomiki okuri-ashi als een alternatieve versie van tsugi-ashi.

- Tsugi-Ashi

- Okuri-Ashi

- Mawari-Ashi

- Ayumi-Ashi

Soms wordt de term “tsuri-ashi” gebruikt in de context van Japanse krijgskunsten en dit creeert dikwijls verwarring in discussies betreffende verplaatsingen.

Tsuri-ashi(つり足 / 吊り足)

Tsuri ashi betekent letterlijk “opgehangen / opgetilde voet”.

In de Japanse krijgskunsten verwijst het naar een manier van bewegen waarbij:

Het gewicht licht en gecentreerd blijft, de voet niet zwaar “neerploft”, je direct kunt reageren (aanvallen, ontwijken, draaien).

Het is dus geen vaste gedefinieerde beweging, maar een kwaliteit van beweging.

In alledaags Japans zegt men niet standaard “hij loopt met tsuri ashi”. het klinkt technisch of vakjargon-achtig.

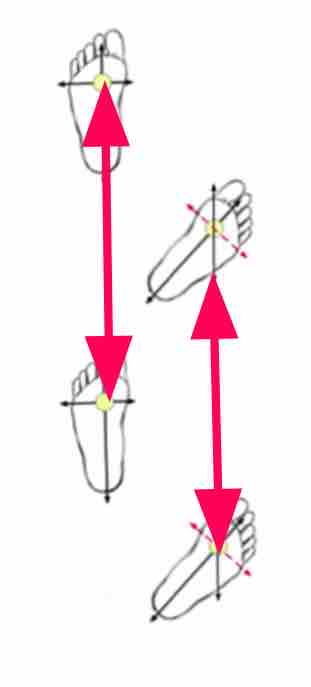

Tsugi-ashi (次足)

Betekenis: “Volgvoet” of “stapvoet”.

Uitvoering 1: Je verplaatst eerst de voorste voet naar voren, gevolgd door de achterste voet die “volgt” om de oorspronkelijke positie te herstellen.

Uitvoering 2: Je verplaatst eerst de achterste voet tegen de voorste voet, gevolgd door de voorste voet om de oorspronkelijke afstand te herstellen. Deze manier wordt gebruikt om de afstand tot de tegenstander te verkleinen. Deze manier leunt sterk aan bij okuri-ashi.

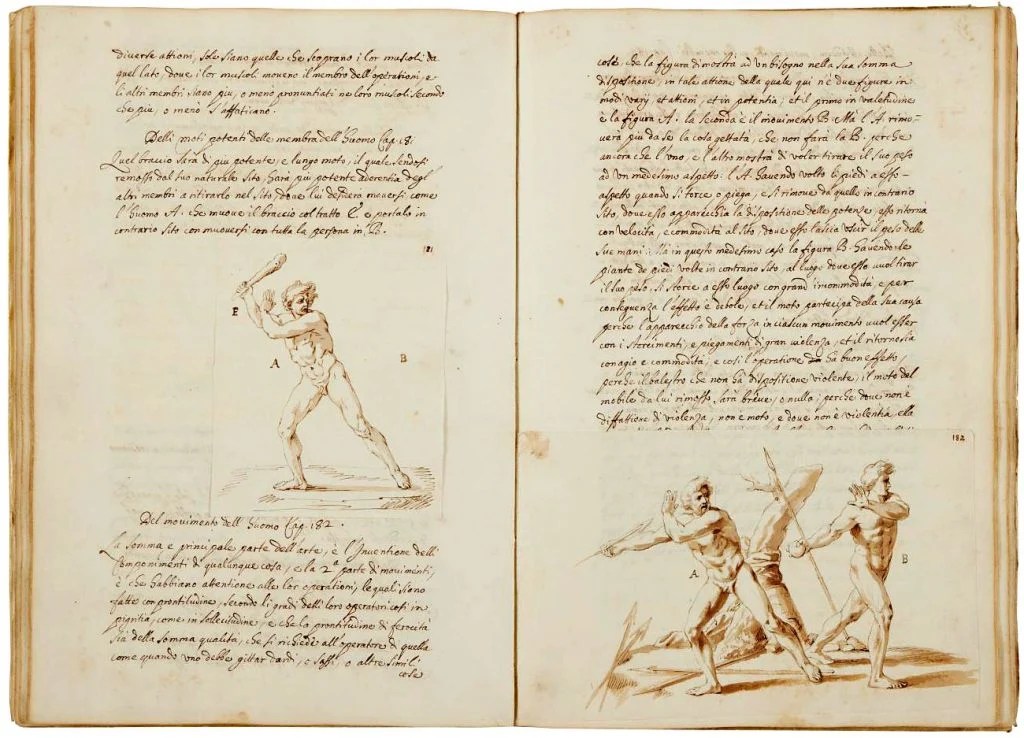

Okuri-ashi (送り足)

- Betekenis: “Duwvoet” of “stuurvoet”.

- Uitvoering: Bij okuri-ashi verplaats je de achterste voet naar voren, terwijl je de voorste voet tegelijkertijd naar voren “duwt” of “stuwt”. Beide voeten bewegen bijna gelijktijdig, maar de achterste voet landt eerst. Dit zorgt voor een krachtige, explosieve voorwaartse beweging.

- Kenmerk: De beweging is explosief en gericht op het genereren van momentum. Het is minder geschikt voor subtiele of defensieve verplaatsingen.

Deze verplaatsing wordt ook als een “uitval verplaatsing” beschouwd en wordt frequent gebruikt in Westerse krijgskunsten zoals schermen en “la Canne” stokschermen.

De achterste voet heeft ervoor gezorgd dat er momentum wordt gecreeerd. Na impact zal men snel tot een normale positie komen

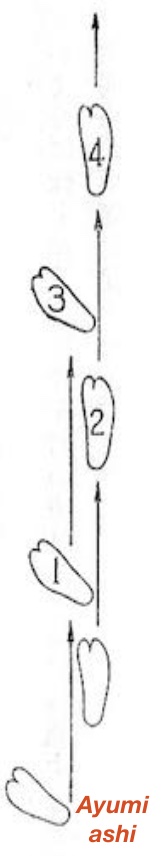

Ayumi-ashi (歩み足)

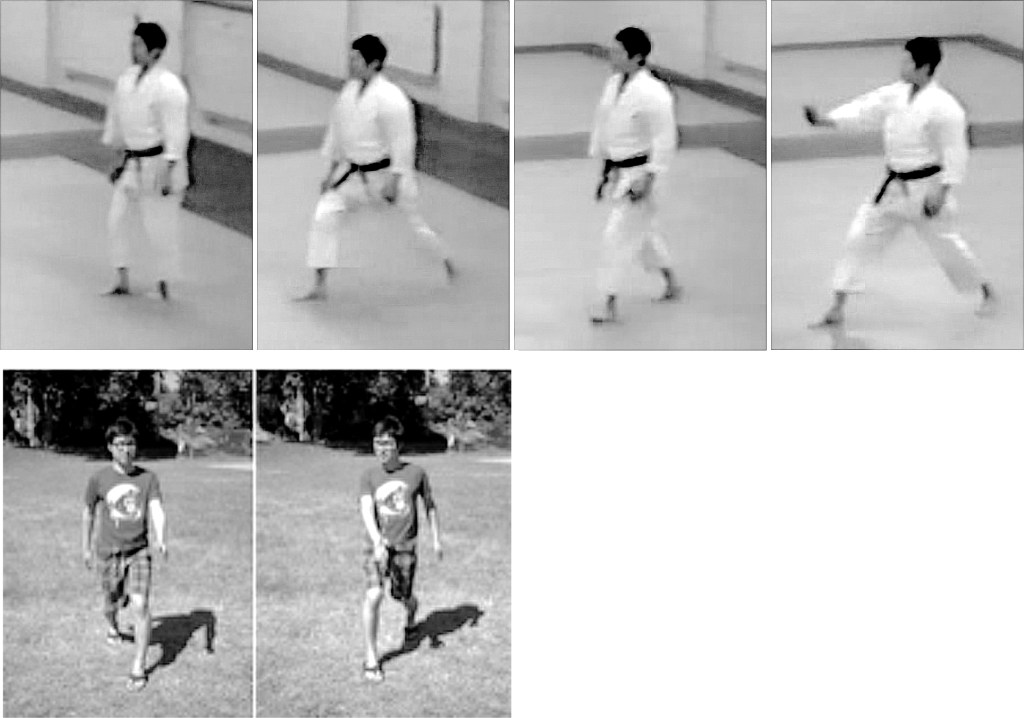

Ayumi-ashi betekent letterlijk “loopstap” en verwijst naar een natuurlijke manier van lopen, waarbij de voeten afwisselend naar voren worden gezet, vergelijkbaar met normaal lopen. Deze staptechniek wordt vaak gebruikt in vechtkunsten zoals kendo, judo, aikido en karate.

Kenmerken:

- De voeten bewegen afwisselend: eerst de ene voet, dan de andere.

- Het zwaartepunt wordt tijdelijk verplaatst naar de voet die naar voren stapt.

- Het is een basisbeweging die wordt gebruikt voor voorwaartse of achterwaartse verplaatsing.

- Ayumi-ashi wordt vaak toegepast in situaties waarbij je grotere afstanden moet afleggen of wanneer je een natuurlijke, vloeiende beweging nodig hebt.

Nanba (難波)

De wandeltechniek nanba of namba, is een traditionele Japanse loopstijl die vooral bekendstaat om zijn efficiëntie, balans en gezondheidsvoordelen. Deze techniek is vernoemd naar de Namba-regio in Osaka, waar het historisch veel werd toegepast. Hier zijn de belangrijkste kenmerken en toepassingen:

Wat is Nanba?

- Oorsprong: Nanba is een natuurlijke, ontspannen looptechniek die stamt uit het oude Japan. Het werd oorspronkelijk gebruikt door boeren, kooplieden en samurai om lange afstanden te lopen zonder vermoeid te raken.

- Kenmerken:

- Korte, snelle passen met een lichte, veerkrachtige tred.

- Minimale verticale beweging, waardoor energie wordt bespaard.

- Gelijke gewichtsverdeling tussen beide benen, wat de belasting op gewrichten vermindert.

- Stille voetplaatsing, waarbij de hiel of middenvoet eerst de grond raakt, gevolgd door een soepele afrol naar de tenen.

Voordelen van Nanba

- Energie-efficiënt: Ideaal voor lange afstanden, zoals pelgrimstochten of dagelijkse wandelingen.

- Gezondheid: Vermindert de belasting op knieën en heupen, wat gewrichtspijn kan voorkomen.

- Balans: Verbeterde stabiliteit, vooral op oneffen terrein.

- Mindfulness: De techniek moedigt een geconcentreerde, rustige geest aan, vergelijkbaar met meditatief lopen.

Nanba is geen standaardterm voor voetbewegingen in traditionele Japanse vechtkunsten. Het kan echter verwijzen naar een specifieke stijl of methode, afhankelijk van de context. In sommige gevallen kan Nanba verwijzen naar Nanba Aruki, een looptechniek die wordt geassocieerd met bepaalde Ninja gevechtsstijlen of militaire trainingen.

Nanba Aruki (難波歩き):

- Dit is een looptechniek die wordt gebruikt in historsche Japanse militaire trainingen en sommige Ninja vechtkunsten.

- Het is een manier van lopen die gericht is op efficiëntie, stabiliteit en het minimaliseren van vermoeidheid tijdens langdurige marsen of bewegingen.

- De techniek benadrukt het gebruik van het hele lichaam om energie te besparen en de balans te behouden.

- In sommige “kata” gebruikt men een gelijkaardige manier om naar de tegenstander te lopen en vervolgens kontakt te maken. In de oude vormen van de Tomiki Aikido kata zal men dit terugvinden.

Geraadpleegde dokumenten:

Judo Taiso – KenJi Tomiki

Nyumon Aikido – Kenji Tomiki

Goshin Jutsu – Kenji Tomiki

Randori no Kata – dr Lee ah Loi

Diverse dokumenten en archiefstukken “La Canne”